Summary

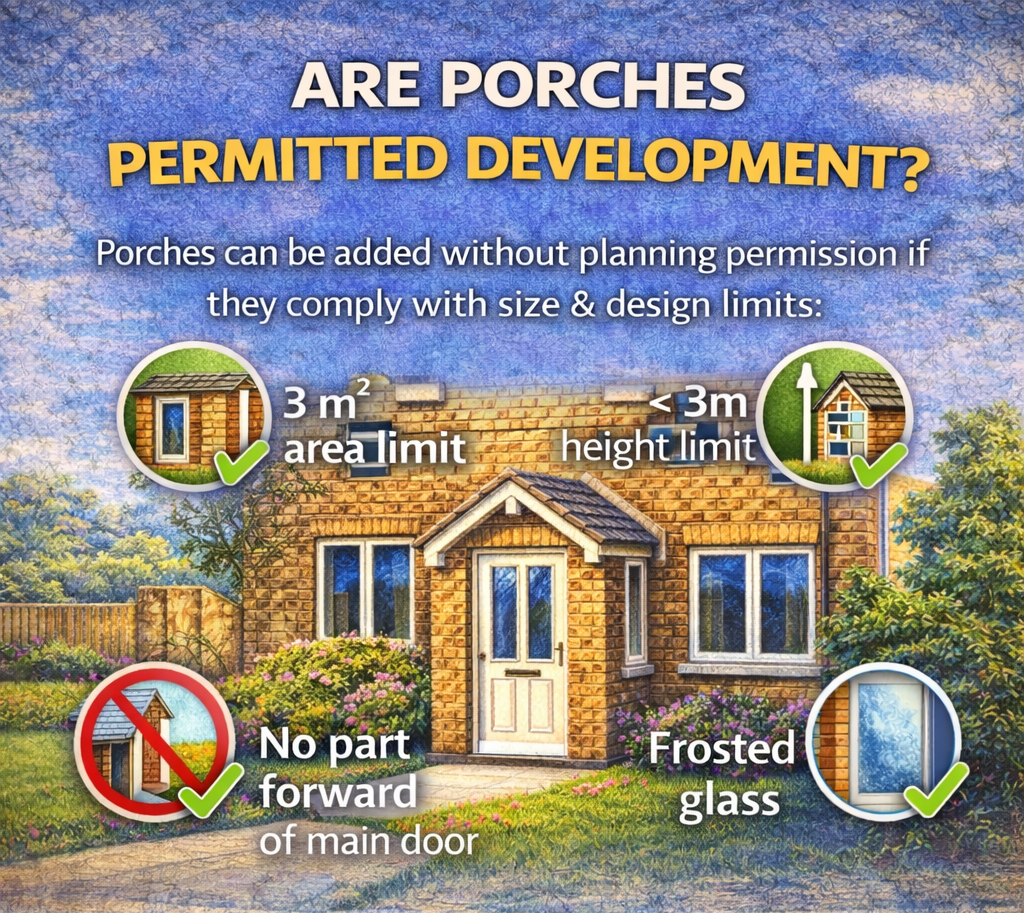

Yes, porches can be permitted development if they meet specific requirements. They must be no more than three square metres externally, no higher than three metres, set back from highways, attached to a house and not restricted by local or conservation policies.

Most homeowners assume a porch is automatically permitted development because it is small, practical, and visually minor – a quick fix for a cold hallway, muddy shoes, or parcels left outside. That assumption is exactly why so many people get caught out. Porches sit at the boundary between private home and public street, and even a modest structure can alter the appearance of the building, disrupt the rhythm of terraces, or introduce features that planning officers scrutinise. The rules are stricter than they look, and the consequences are real.

From a planning perspective, a porch is treated as an extension to the dwellinghouse once it is enclosed, has walls, glazing, and a roof, and is fixed to the building. Simple canopies or door hoods may avoid classification, but as soon as a porch is enclosed, permitted development rules apply.

For a porch to qualify as permitted development, it must meet strict conditions. The external ground area cannot exceed three square metres, measured from the outside face of the walls. Wall thickness, detailing, and decorative features quickly reduce usable space, so many porches that appear compliant on drawings end up exceeding the limit once built. Height is capped at three metres, including any roof ridges or parapets, and any part of the porch within two metres of a highway boundary – including pavements, footpaths, and some shared access routes – invalidates PD rights. These distances are measured from the legal boundary, not fences or walls. Finally, permitted development rights only apply to houses; flats and maisonettes do not qualify, even if they have a separate ground-floor entrance.

Properties in conservation areas, national parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, or other designated land may lose PD rights entirely. Porches in these areas are particularly sensitive because even a small structure can disrupt established proportions, obscure original architectural detailing, or introduce materials that feel out of place. Looking at a neighbour’s porch for guidance is unreliable – it may have predated current policies, been granted planning permission, or been unauthorised.

Here’s the reality that most articles don’t tell homeowners: three square metres is not enough space. Once wall thickness is considered, usable internal space shrinks further. Door swings alone can dominate the layout, and adding coats, shoes, parcels, or a pushchair can make a PD porch feel cramped, awkward, and underwhelming. Many homeowners design to PD limits purely to avoid planning permission, only to find the result fails to solve the problem they started with. Saving a planning fee often comes at the cost of usability and comfort.

Builders often reassure homeowners that a porch is permitted development, but this advice is not a guarantee. Builders are not responsible for planning compliance, and PD interpretation is rarely part of their contractual role. If a porch later turns out to require permission, the homeowner remains liable. Understanding this early avoids misplaced confidence and costly mistakes.

The instinct to avoid planning permission is understandable – fees, paperwork, and delays can feel like obstacles. But the trade-off is rarely worth it. A permitted development porch may fit within the rules, but it often compromises on space, proportion, and function. Designing a porch properly, even if it requires planning permission, usually results in a far more useful and aesthetically coherent addition.

Planning permission is not a punishment; it is a design opportunity. It allows a porch to be proportioned correctly, designed to suit the house, and integrated with the street scene. Properties with sufficient setback from the street, or where the porch is subordinate to the main house, often have a high chance of approval. Planning officers are concerned with scale, proportion, and impact, not simply denying additions.

Enforcement is usually complaint-driven but can arise at any time, particularly during property sales. Solicitors increasingly ask for proof that additions were lawful. Without planning permission or a lawful development certificate, even a small porch can delay or complicate a sale. A lawful development certificate is not compulsory, but it provides certainty and removes doubt for future buyers. Most porch problems arise not from ignoring the rules, but from prioritising avoidance over usability.

Porches can be permitted development, but the limits are real, and 3 square metres is often insufficient for practical use. Homeowners who design solely to fit PD limits risk creating an addition that is cramped, awkward, and ultimately fails to solve the problem they were trying to fix. Rather than asking how to avoid planning permission, the right question is what kind of porch genuinely improves the house. A properly planned porch, whether permitted development or through formal planning, will work, look appropriate, and avoid costly mistakes in the future. Thinking through design first ensures the porch truly enhances the home rather than simply ticking a regulatory box.

Studio FRI is a contemporary architectural and planning practice based in Preston, working across Lancashire and the wider North West. We specialise in refined residential architecture and strategic planning, delivering calm, considered design solutions shaped by insight, proportion and purpose.

Cotton Court Business Centre, Preston PR1 3BY

©2026. Studio FRI All Rights Reserved.